Out with the Swiss consultant. In with the community of local drone experts!

Disclaimer: a lot of the theory and rationale behind this are the brainchild of my good friend and colleague, Ivan Gayton. I owe a lot of this content to discussions with him in the field!

Background

Why do we need drone imagery

In short, there are no other good alternatives:

-

Imagery is the foundation of an end-to-end mapping chain, from capture --> processing --> digitisation --> field mapping --> publishing and data access.

-

Sure, OpenStreetMap is an incredible resource. But without up-to-date, high-quality imagery available, we are limited for how accurately the digital map can reflect the true reality:

-

Launching a satellite isn’t in the realm of possibility for most countries, let alone communities.

-

Even purchasing satellite imagery isn’t in the realm of mere mortals. Unless you are happy to drop multiple 10 of 1000’s of $$$ to acquire imagery, with no guarantee a vendor would even humour your puny purchasing power compared to large corporate entities.

-

Drone hardware and software has moved at an incredible pace over the years - some of the ‘cheap’ drones - once considered toys - are now viable for professional quality data acquisition and output.

-

Along with our partners at NAXA in Nepal, HOTOSM has built a digital public good called Drone Tasking Manager: a tool for coordinating imagery capture amongst a team of local drone operators. See this blog post, by one of the main developers, Niraj Adhikari.

Note

If you didn’t know already, I’m currently the tech lead @ HOTOSM. But don’t worry, I’m not trying to sell you crap.

All of our tools are fully open-source, community driven, and built to empower, not to extract profits from, those that truly need it.

How this has been done in the past

-

If you are serious about collecting drone imagery for your region, most INGOs would requisition an expensive consultant to travel to the area of need, expensive high-end equipment in tow, in typical neo-colonial ‘look at the fancy tech we can afford’ style.

-

The consultant oversees the capture of automated large scale imagery capture, with a ‘professional’ mapping drone:

The fancy-pants Wingtra One fixed wing drone, which can fly an advertised 4km² in a single flight. Don’t worry, it only costs US$20,000.

-

This sort of equipment is perfect if you are optimising for high labour costs. It’s the typical model of drone manufacturers, where they are continually innovating to reduce the amount of time to operate the drone. However, this does not apply in regions where labour is cheap, but purchasing power is low - a large chunk of the world (we don’t mind if it takes a few extra days to collect imagery, as long as we can afford to do so).

-

Instead, we propose a workflow based entirely on small <250g consumer-grade drones, typically sub $1000, a price possible within reach of a community of passionate mappers, a local government, or even individuals in upper-middle income economies.

-

Consider that within the cost we are also skilling up the local workforce, benefiting the economy and local families, and avoiding a reliance on consultants to continually come back and re-fly. For the price of one Wingtra One, a community could equip 20+ local operators in this manner.

What kind of drones are we talking about here?

- DJI - the largest drone manufacturer in the world - has been pushing out some top quality low end quad-copter drones in recent years, such as the DJI Mini 4 Pro.

Note

The DJI Mini 5 Pro was released not long ago, and is an incredible piece of kit. Not only does it have a 1" CMOS sensor for better imagery capture in reduced light conditions (i.e. not the middle of the day), it also has a dual frequency GNSS receiver: for the layperson, this means the potential for extremely accurate geopositioning of the captured imagery - professional drone survey level accuracy.

-

Despite the high likelihood of DJI sending encrypted packets containing user data back to China, these drones are top tier for our use case, and frankly we have bigger concerns: producing quality geospatial datasets capable of informing humanitarian, disaster management, and general digital data empowerment amongst the communities we serve.

-

The key reason I mention the <250g caveat above, is that this is often the limit specified by most aviation authorities globally, in which a drone moves from a ‘hobby’ tool without any real danger, into a potentially weaponisable piece of kit that should be strictly regulated.

So what are we doing right now?

The Karangesem BPBD disaster agency

-

I’m currently writing this from Amlapura, a city that houses the regional disaster management agency, and our key local partner, Pika.

-

Ivan (mentioned above), formed a relationship with Pika and the BPBD a few years ago, and since then we have worked with them to develop a global center of excellence for open mapping and disaster response in the region.

-

The staff at the BPBD have been incredibly accommodating, and most importantly, eager and passionate about learning to use the technology that could assist with crucial disaster preparedness activities.

-

Not only does Bali have some of the most relaxed visa requirements and drone regulations globally, this easy-going and giving nature emanates from the people here too: nothing is ever a problem, from getting permissions to fly, interacting with local community leaders, to lunch being provided gratis to their guests (us) every day! We are truly indebted to the BPBD for their kindness and for facilitating this incredible initiative 🙏

The Center of Excellence

-

The idea here is to firstly capacity build the disaster response capabilities of the local agency here, and eventually over all of Bali.

-

The ‘Center of Excellence’ is also a training ground: any individuals from around the world - we currently are accompanied by colleagues from East Africa, but eventually we hope to have people from every continent visiting this office - will come here to learn how to coordinated waypoint missions within teams.

-

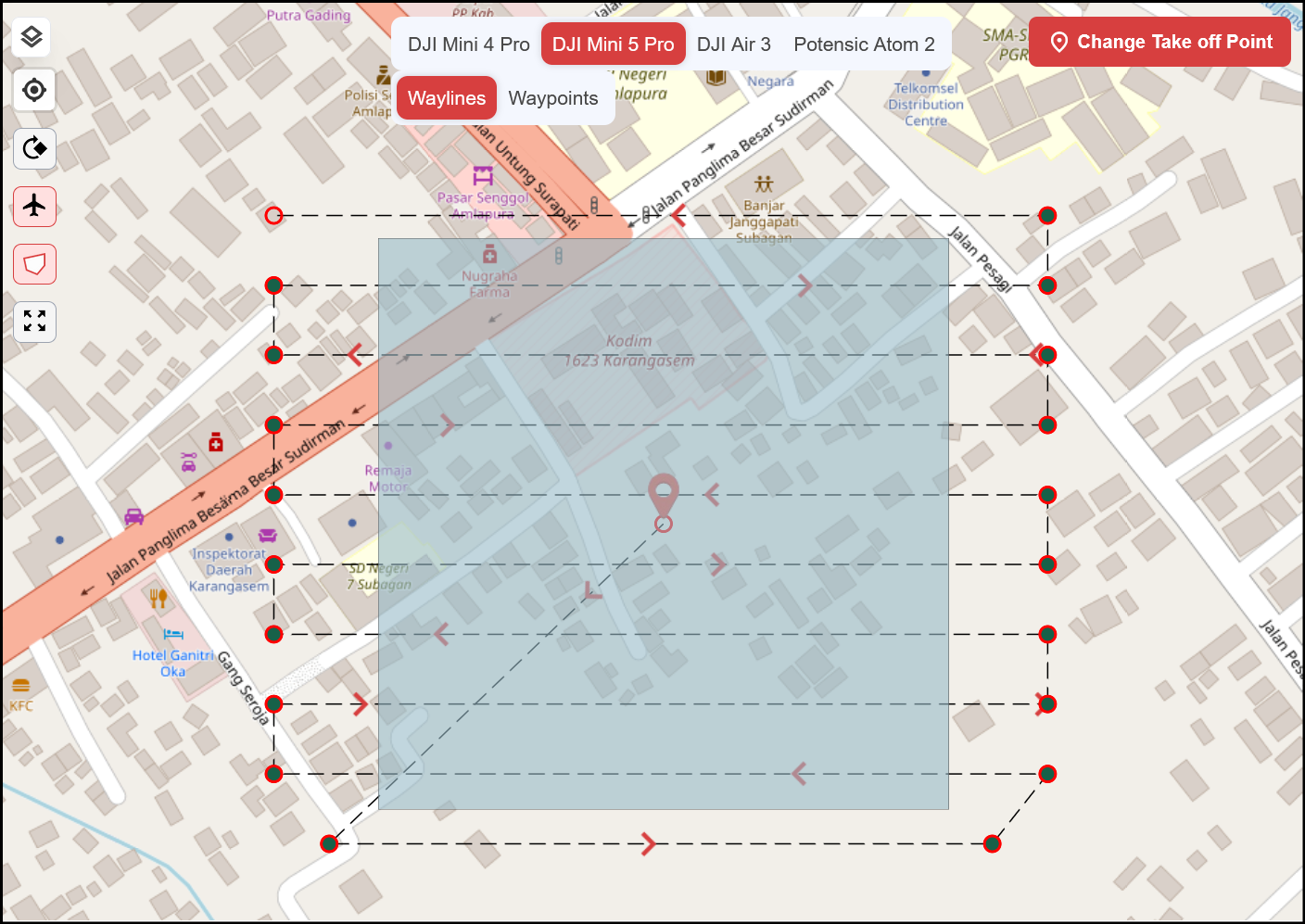

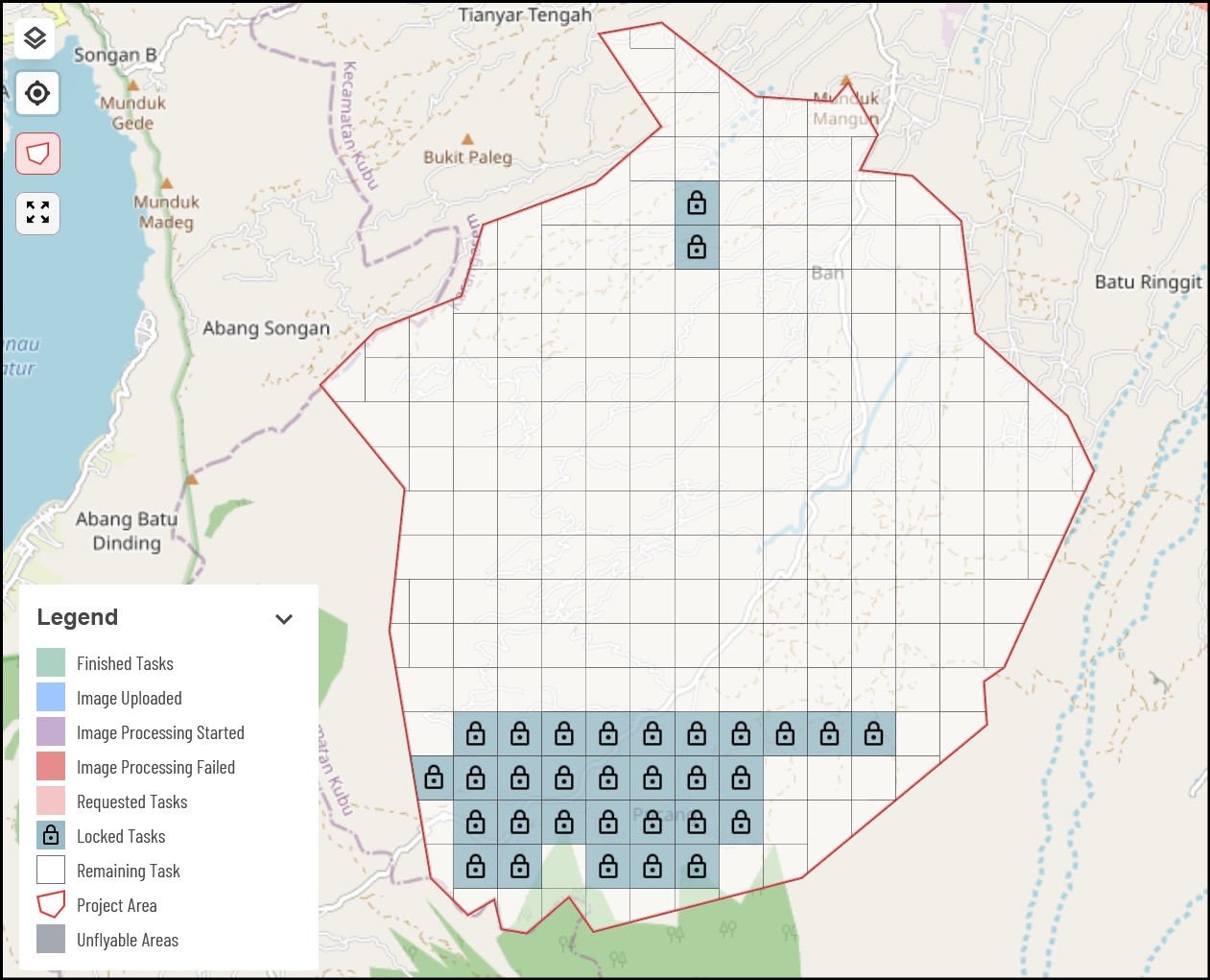

These ‘waypoint’ missions allow us to systematically capture drone imagery over a single task area, ideally in a single flight on one battery. Capturing a whole bunch of adjacent tasks in a grid quickly leads to an entire project area being covered in no time, by a team.

Mapping evacuation routes and monitoring stations on Mt Agung

-

One of the core tenets of the ‘center of excellence’ is that we should carry out actual meaningful work.

-

With that in mind, and following a few days training and skillshare between HOT tech, HOT Asia Pacific Hub, and the BPBD Karengesem, we will be undertaking a mapping exercise around the slopes of Mt Agung volcano.

-

The purpose of the exercise is to collect drone imagery (obviously!), to aid the identification of possible evacuation routes, and also find suitable locations for the placement of early warning stations.

The area we will fly tomorrow, Ban, on the NW slopes of Mt Agung

A quick aside about QField

-

Recently, we have been assessing the use of QField integration into the Field Tasking Manager.

-

During our training and flight tests in different parts of Karangesem, there was one key aspect that was bothering me about the workflows in Drone Tasking Manager: the need to work offline.

-

Currently the tool is web based, requiring an internet connection to access tasks and generate flightplans - not ideal for remote field activities!

-

You may think: why not just generate all the flightplans in advance, then go to the field? This would be possible, if we didn’t need to adjust the take off point for each flightplan we generate.

-

The reason for this is twofold:

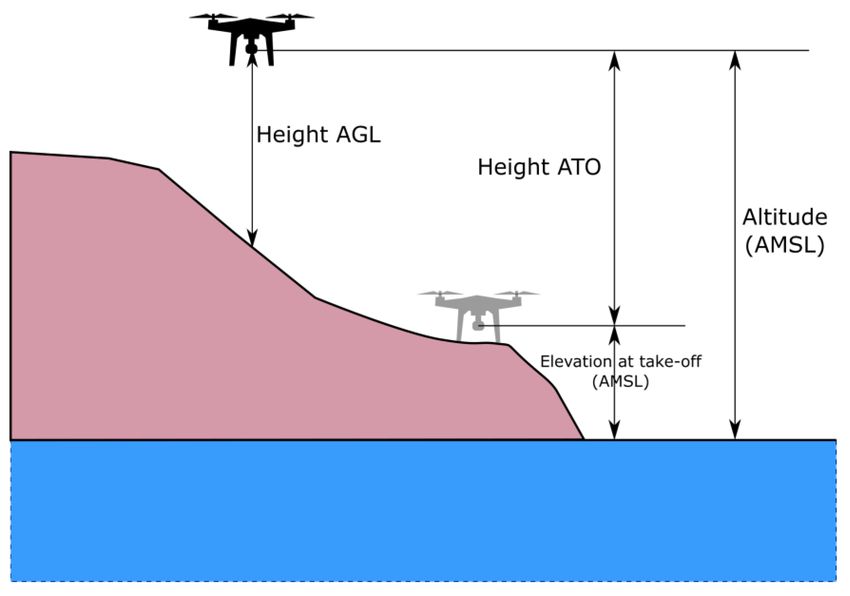

- Terrain following is set by altitude above ground level (AGL). In order to calculate this, we need to know the altitude of the takeoff point, then calculate the relative height the drone needs to fly. If we don’t do this, we risk the drone flying at the wrong absolute altitude, potentially crashing at worst, or having inconsistent final image resolution at best.

- Selecting the takeoff point in advance is not easy, considering road access, terrain and vegetation.

- The experience got me thinking: why not use QField to assist with the offline coordination. An individual or team could go on a scouting mission to identify suitable takeoff points (ideally high ground in hilly terrain, with unobstructed views for multiple surrounding tasks).

Note

Obviously this is only a temporary workaround, while we create workflows that allow for entirely offline flightplan generation. If operators can do this, there is no need to pre-identify takeoff points.

We had some idea for how to do this directly in QField, so stay tuned for updates on that front.

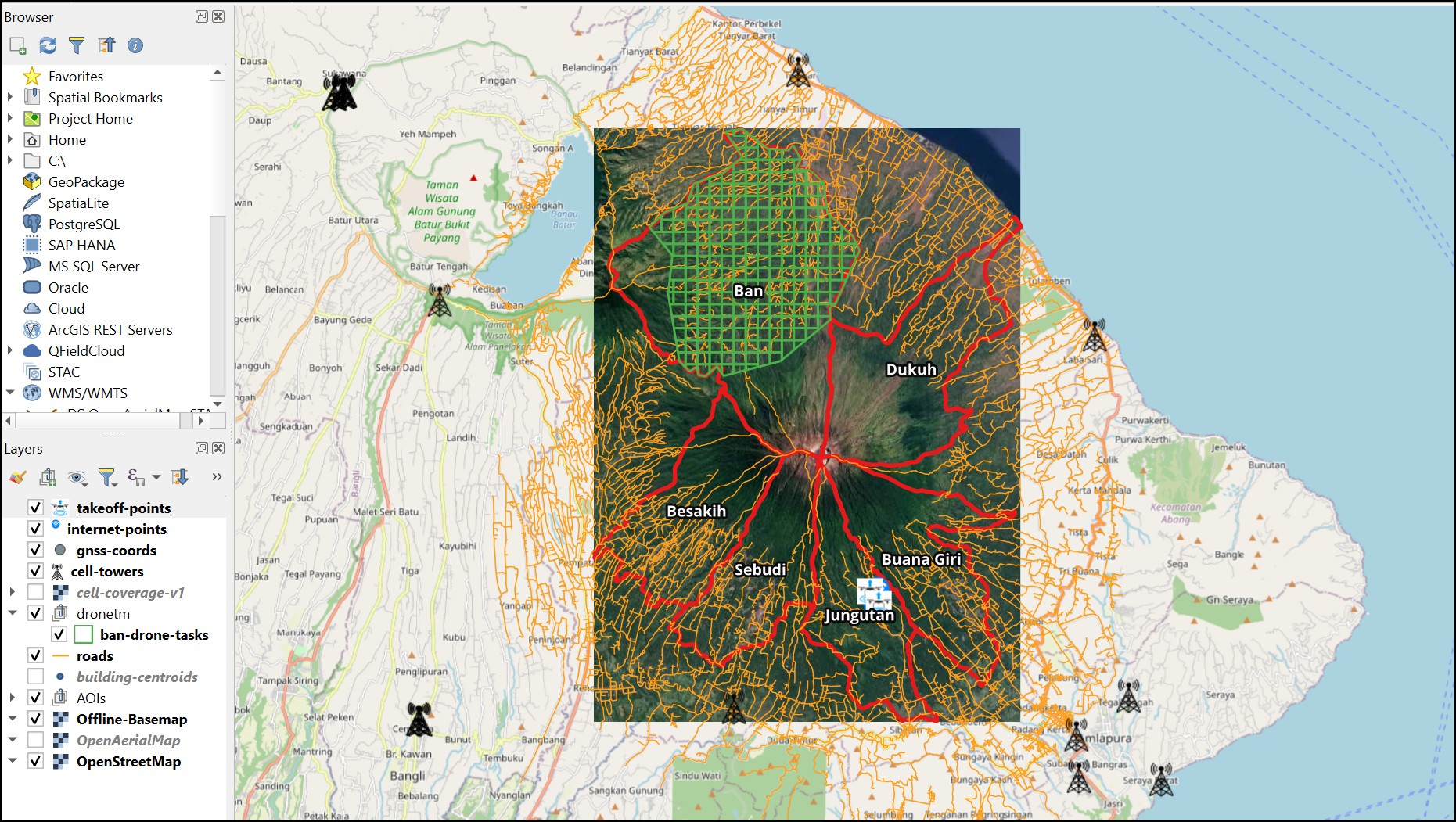

- I created a QField project, synced to QFieldCloud between the team, containing a basic offline satellite imagery layer, cell tower locations, and georeferenced signal map from GSMA, OSM roads and buildings, DroneTM flight task grids, and finally some layers to add points, comments, and photos of internet / take off points:

Note

This blog was written in two parts. The following is from after the field activities.

Retrospective

How did it go?

-

Overall, a great success!

-

By the end, the teams felt confident with the workflows in place, being able to capture a large area of collective imagery in a single day.

-

Identifying the high points and marking them on QField worked really well.

A location we could fly at least 6 tasks from, with a great field of view over the adjacent mountain to Agung. There was a great warung nearby too with some of the best vegetarian food I had in Bali!

- Obviously I was woefully unequipped to handle the mountainous trails on my hired Yamaha NMax, but we managed to cover all the ground:

- Capturing imagery of some pretty hidden buildings that are now on the map and easily identified for disaster response!

Software developers must go to the field

-

I’m going to estimate that gathering feedback on the real pain points first hand can save months of potential misguided development time.

-

Mappers tend to come up with pretty creative solutions to solve the problems they encounter. Sometimes these solutions give ideas to improve a tool, other times they may go unnoticed as operators don’t realise it could be done another way and don’t think to complain. Being there to witness this is key.

-

Two failure modes of DroneTM identified:

- The loss of signal behaviour was incorrectly configured. This is fine in flat terrain. In hilly terrain, teams often lost signal with the drone temporarily, triggering a return to base and abort of the current mission. The only option is to do a fiddly waypoint deletion workaround, or refly. We managed to fix this by tweaking the DJI WPML files!

- Flightplan generation must be offline. We knew this already, but it really hammered the point home.

Summary

Community drone mapping is the culmination of forces - high quality consumer grade drones, cutting-edge opens-source software, and community participation and empowerment to generate their own geospatial insights.

As momentum for this approach builds, we are steadily approaching a goal to capture imagery on a regular basis for cities and communities globally, regardless of purchasing power for the ‘professional’ stuff, and specific in depth expertise for drone flying or imagery processing.

With high quality 3D point cloud data now at our disposal, and unprescendented imagery quality for general open datasets, let’s map our world anew into the next decade!